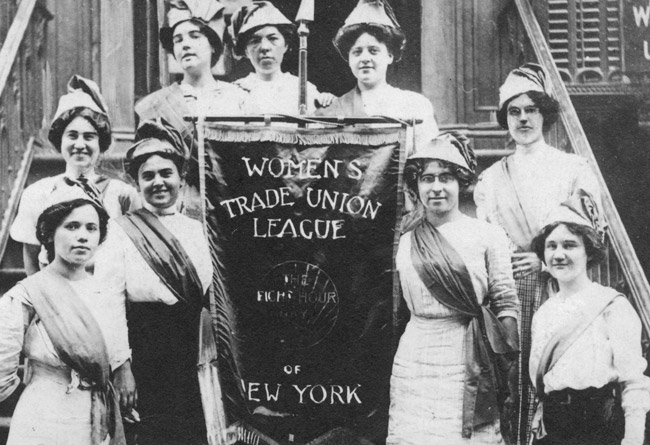

In response to the abysmal working conditions in factories, large numbers of garment workers began to discuss their unhappiness about working long hours, for so little, and in an unsafe environment. Labor unions, organized groups of workers who join together giving them power to negotiate working terms and conditions, began to form in the United States around the mid 19th century, yet many did not include women or unskilled workers. It was not until 1900 that the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) was founded to improve working conditions and offer protections for women, the majority of whom were immigrants working in garment factories. Labor unions offered promise for change and many immigrant workers began to join the union and strike for better conditions.1 Rose Cohan tells of the factory she worked in and her experience joining a union in Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side. The men in the factory she worked in joined the union and she describes watching them leave at 7 in the evening while the women who were not part of the union were left to work into the night.2 Rose Cohan’s father who had also joined the union, came home one night and told her, “you too must join the union.”3 She attended a meeting where a speaker called on the crowd to demand better working conditions, shorter work weeks, wage cuts and safety protocols for their labor.

Each one of you alone can do nothing. Organize! Demand decent wages that you may be able to live in a way fit for human beings, not swine. See that your shop has pure air and sun, that your bodies may be healthy. Demand reasonable hours that you may have time to know your families, to think, to enjoy. Organize! Each one of you alone can do nothing. Together you can gain everything.4

After this speech Rose Cohan, like thousands of other Jewish immigrant women in the garment industry, joined the immensely popular union demanding better working conditions such as access to light and heat, compensation in the event of injury, and to not have to work outrageous hours for barely sufficient pay. At union meetings they listed their grievances about long work weeks that could often be up to 75 hours, wage cuts, and unsafe conditions in the factories and called for action for change.5

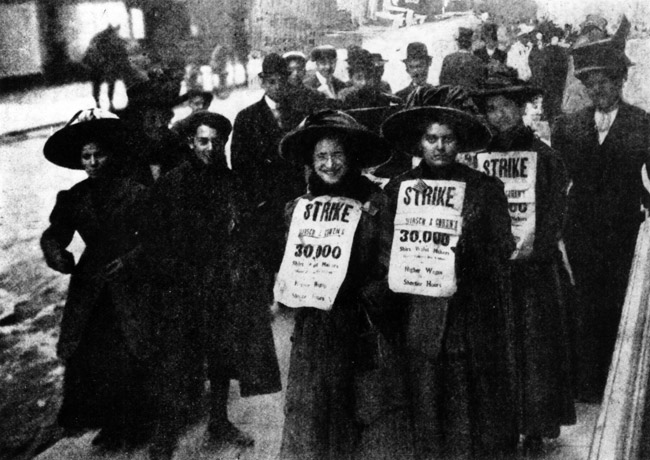

On November 22, 1909, at a ILGWU meeting, Clara Lemlich made her way to the podium and gave a rousing, agitational and unplanned speech in Yiddish.

I am a working girl. One of those who are on strike against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in general terms. What we are here for is to decide whether we shall strike or shall not strike. I offer a resolution that a general strike be declared now.6

Her passionate speech inspired over 20,000 immigrant women garment workers to go on strike. Their demands called for a 52-hour work week, union-exclusive contracting and higher pay.7 Women workers in the garment industry had struck before yet, The Uprising of 20,000 as it came to be known, was significant due to the substantial numbers of workers who participated and the popularity and power of unions, and ended two and a half months later in 1910 with the signing of the notable Protocol of Peace.8 This compromise between ILGWU leaders and factory bosses proposed better working conditions and labor rights in factories in exchange for workers returning to the shops. The Protocol of Peace stipulated agreements such as: standard minimum wages for different garment jobs, double pay for overtime, 50 hour, 6 day work weeks with either Saturday or Sunday off in accordance to an employee’s religion, vacation for official US holidays, and installation of electricity without workers being charged.9

Unionizing helped to create a sense of belonging in the United States, a sense of being a part of society instead of just being an Other. The steps taken to be in a union and participate in a strike were American activities, and this partaking was in itself a form of Americanness. At this historical moment only White men had full participation in freedoms promised by the US Constitution, and were by that skewed logic, in all respects American. Yet, immigrant workers used the very system that was built to Other and excluded them from being seen in society as fully American, to build themselves up, to create for themselves the American vision imagined and talked preceding their arrival in America. The First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech and right to assemble and immigrant garment workers used these protections to unionize, part of the process in their Americanization and assimilation in an effort to be seen as White by the dominant society. At the same time they were also creating their own histories as Jewish and Italian Americans.

1. “Strikers And Stylemakers,” Tenement Museum, 2020, https://www.tenement.org/strikers-and-stylemakers/.

2. Rose Cohan, Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side, Documents in American Social History (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995), 124.

3. Ibid., 124.

4. Ibid., 126-127.

5. “Strikers And Stylemakers,” Tenement Museum, 2020, https://www.tenement.org/strikers-and-stylemakers/.

6. “Clara Lemlich And The Uprising Of The 20,000,” American Experience, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography-clara-lemlich/.

7. Ibid.

8. Michael Keene, with Hasia R. Diner, “The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire,” Podcast. Talking Heart Island, 2019. https://talkinghartisland.podbean.com/e/the-triangle-shirt-waist-factory-fire-with-hasia-diner/.

9. ILGWU, “Protocol Of Peace” (Labor agreement, repr., Cincinnati, 1910), Rare documents file and Louis Marshall Papers, The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives. http://americanjewisharchives.org/exhibits/aje/_pdfs/E_59.pdf.