White American society viewed the Jewish immigrants living in the Lower East Side tenements as Others but were also very curious and came into their community to observe. Immigrants were viewed, written about and photographed in response to great curiosity about their cultures, traditions and living conditions. In Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side, Rose Cohan describes being hospitalized by White Americans and wondering why she was receiving this attention. “I did not know that the part of the city where I was living was called the East Side, or the Slums, or the Ghetto, and that the East Side, or the Slums, or the Ghetto was still new and a curiosity to the people in this part of the city.”1 The media surrounding the Lower East Side propagated the notion that Jewish people were Others. In a letter to the editor appearing in The New York Times in 1899 titled “Romance VS. Reality,” the author who went by the byline J.F.F. argued that the picture painted by Jacob Riss, a journalist, photographer and ‘muckraker’ – advocate for social reform who exposed corruption – saw the Lower East Side “through a rose colored glass” when he described its “picturesqueness and humor.”2 In his letter to the editor he writes,

Instead of humor I found – dirt; instead of picturesqueness – squalor and reprehensible neglect of the commonest laws of decency… filth, quarrel… noise and noxious orders alternate and fill up the gamut of these people’s lives.3

While some considered Jewish immigrants a threat to White America because of their difference in culture and the impoverished part of New York City they lived in, others saw an opportunity to advocate for social reform. Reformers who had no knowledge of Jewish culture or traditions worked to aid immigrants’ living conditions and provide education and health services. These reforms however, were also an attempt to remake Jewish people as ‘more’ American by encouraging their participation in Whiteness. Jewish immigrants were taught English and White American social customs and norms in schools, settlement houses and hospitals. Many reformers were also missionaries who misused Christianity as a way to ‘save’ the Other. Rose Cohan tells how her siblings Leah and Ezekiel went to a school that was run by a missionary society. “Any child in the class who would say a prayer received a slice of bread and honey.”4 She also tells of when she went to a hospital set up by reformers for poor people and immigrants, who had raised funding through the pictures and articles about the Lower East Side. At the hospital everyone only spoke English. Rose Cohan tells that “on Monday afternoons a missionary used to come to our ward…. she would give out Hymn Books” and “Began to talk about Christ.”5

There were also many social workers and reformers who feared young unmarried Jewish immigrant women’s perceived immorality and tried to set these young women on a path of virtuous Americanness.6 In an article from the New York Times titled “New York’s Biggest Problem, Not Police, But Girls; Immodesty, Extravagance, and Ignorance Are Among Their Characteristics, Says Miss Trenholm, Head Worker of the East Side Settlement,” published in 1912, Miss Trenholm, the head worker at the East Side Settlement House – an institution established to provide educations for those in need – discussed reform and young immigrant women. She states that “the problem of the health, the morals, and the education of our” immigrant “girls is the greatest lot which now confronts us… the modern very poor New York girl is not a modest girl.”7 Although reformers were helping improve the conditions in tenements and provide education for immigrants on the Lower East Side, they did not understand Jewish culture or traditions and their reforms were a way for White society to lessen the fear of the Other and propagate White Supremacy.

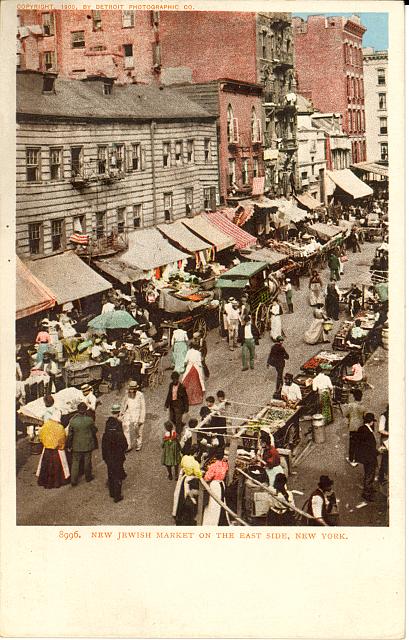

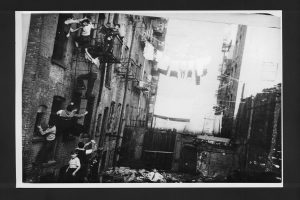

Photographers went to the Lower East Side to capture foreignness, poverty and dirt.8 There are pictures of bustling crowded streets filled with pushcart vendors and women who wore wigs, there are rundown buildings and cramped rooms and children who look dirty. These photos are only snapshots of the Lower East Side taken from an outsider’s perspective, a single moment in a lifetime. The viewer sees the poverty, overcrowding and grim conditions, yet does not see the lives lived, and there are few pictures of joy or celebration thus dehumanizing those who lived there. These photographs don’t show the perspectives of immigrants who are looking around but show the perspectives of White American’s who are looking in. “The photographers see selectively because they are outsiders,” writes Deborah Dash Moore and David Lobenstine in “Photographing the Lower East Side: A Century’s Work.”9 The pictures that can be viewed give access to the past, but in a narrative not by those who lived on the Lower East Side or who were Jewish immigrants. There are some immigrant testimonies and public records but the majority of the sources used to teach about and understand the Lower East Side during the late 19th and early 20th centuries comes from White Americans. Today the pictures show a place of memory, but only a snapshot of what once was a much more colorful joy filled space.

1. Rose Cohan, Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side, Documents in American Social History (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995), 240-241.

2. “Romance VS. Reality,” The New York Times, May 23, 1899, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1899/05/23/117922016.html?pageNumber=6.

3. Ibid.

4. Rose Cohan, Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side, 160.

5. Ibid., 242-243.

6. Riv-Ellen Prell. “The Ghetto Girl and the Erasure of Memory,” in Remembering the Lower East Side: American Jewish Reflections, ed by Hasia R. Diner, Jeffrey Shandler, and Beth S. Wenger, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), 94.

7. “New York’s Biggest Problem, Not Police, But Girls; Immodesty, Extravagance, and Ignorance Are Among Their Characteristics, Says Miss Trenholm, Head Worker of the East Side Settlement,” The New York Times, August 4, 1912. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1912/08/04/issue.html.

8. Deborah Dash Moore and David Lobenstine, “Photographing the Lower East Side: A Century’s Work.” In Remembering the Lower East Side: American Jewish Reflections, ed by Hasia R. Diner, Jeffrey Shandler, and Beth S. Wenger, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), 30.

9. Ibid., 30.