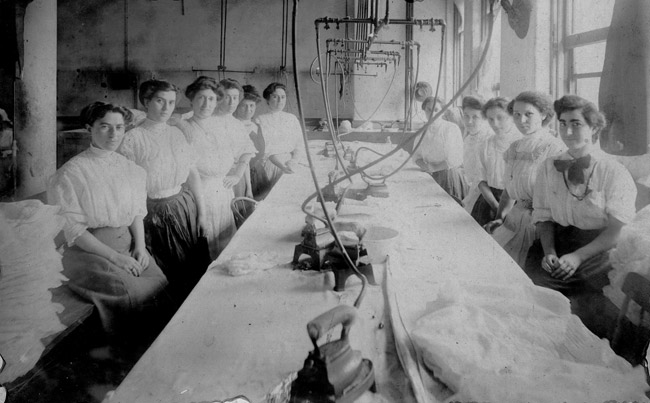

The vast majority of young Jewish immigrant women found jobs in the garment industry. They began learning English, could pick up factory skills quickly and were able to easily find employment. Although they did not make a lot of money, these young women were often the main breadwinners for their families. Their fathers generally had a harder time finding work in factories as they often did not learn English as quickly and many tried to earn a living selling food or goods from push carts on the Lower East Side. Their mothers in most cases did not work but stayed home fulfilling the traditional gender role of taking care of the home. While the majority of their earnings went to help their families, young women were able to save a little for themselves. On factory floors young immigrant women made new friends and conversation flowed as they talked about spending their extra money on American activities such as going to the theater or movies, frequenting dance halls and taking trips to Coney Island.1 Their jobs gave them both economic freedom and the ability to participate in American society and culture. Sadie Frowne, a young Jewish immigrant, tells of her experience working in the garment industry and living on the Lower East Side in the Independent on September 25, 1902.

The machines are all run by foot power, and at the end of the day one feels so weak that there is a great temptation to lie right down and sleep. But you must go out and get air, and have some pleasure. So instead of lying down I go out… I am very fond of dancing and, in fact, all sorts of pleasure. I go to the theatre quite often, and like those plays that make you cry a great deal. ‘The Two Orphans’ is good. The last time I saw it I cried all night because of the hard times that the children had in the play.2

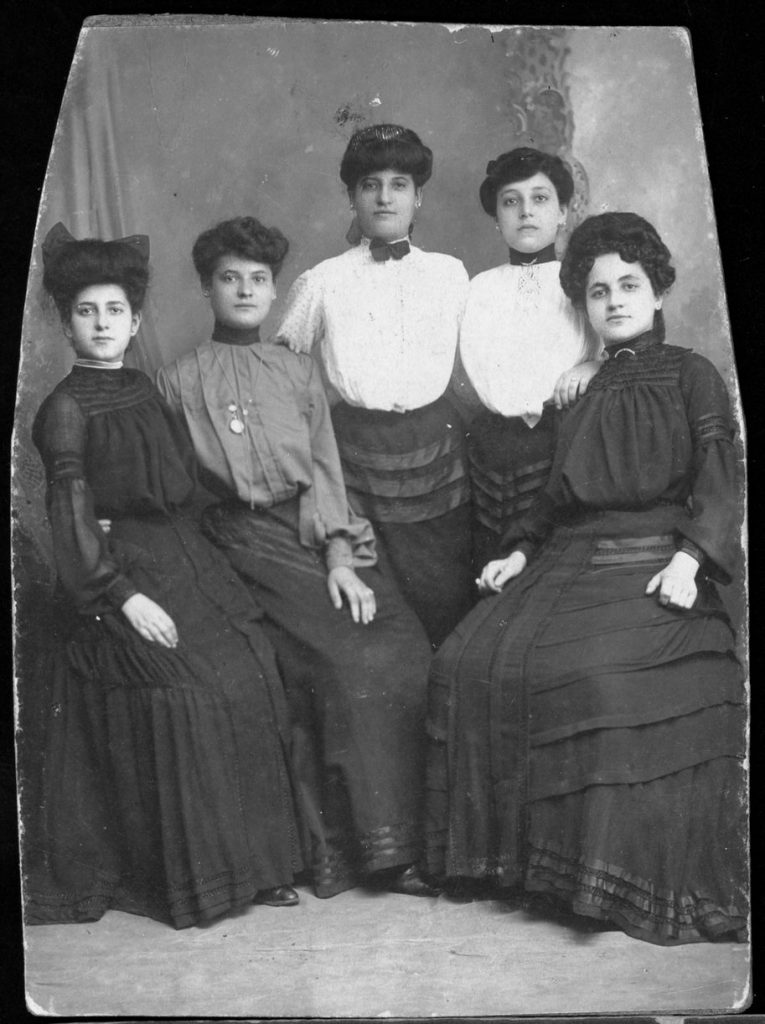

As they sewed garments, the young women talked about new fashion and cosmetics as they began to dress like ‘American’ women -White protestant women who spoke English and whose families had been in the United States for some time – who bought and wore the clothes they made. Through fashion, a cultural and societal signifier, these young women tried to become ‘more’ American. “A girl must have clothes if she is to go into high society at Ulmer Park or Coney Island or the theatre,” tells Sadie Frowne, “a girl who does not dress well is stuck in a corner, even if she is pretty.”3 Her testimony also shows the pressures of being a woman, and expectations of femininity and beauty at this time.

Although young Jewish immigrant women did not have enough money to buy the expensive clothes they made that were sold on 5th Avenue, they wore cheaper ready-made or handmade clothes. The cheaper style was noted and disapproved of by White Americans. In an article in the New York Tribune in 1900, a journalist stated that, “if my lady wears a velvet gown, put together… in a East Side [sweatshop]… the girl whose fingers fashioned it,” will surprise “Grand-st. with a copy of if on the next Sunday? My lady’s is in velvet, and the East Side girl’s is in the cheapest of cloth.”4

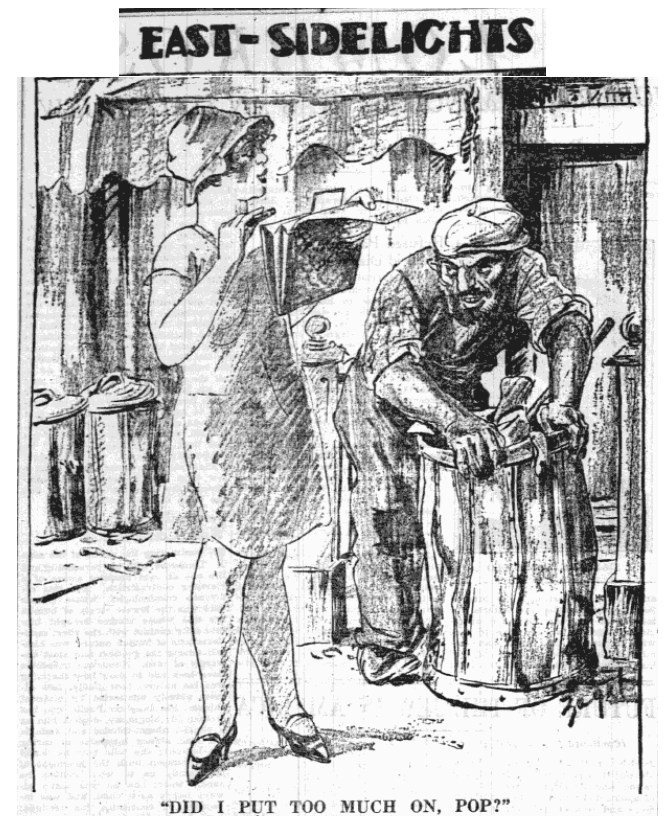

Young Jewish immigrant women were often called ‘Ghetto Girls,’ a name that originated from the Lower East Side being called the Jewish Ghetto. They were dubbed tacky, outlandish and even vulgar by White Americans who claimed their dresses were over the top, and that they wore too many bows, too much jewelry, and too much makeup. In “New York’s Biggest Problem, Not Police, But Girls; Immodesty, Extravagance, and Ignorance Are Among Their Characteristics, Says Miss Trenholm, Head Worker of the East Side Settlement,” an article in the New York Times from 1912, Miss Trenholm tells of what she believes is poor taste, “see the ribbons. They are not beautiful or do they encourage a love of beauty.”5

These thoughts about the fashion worn by the ‘Ghetto Girls’ being tasteless and over the top were also shared by other, and often older, Jewish people who believed these young women were too modern. Young Jewish immigrant women faced dual pressures from oppositional forces about their dress and sense of belonging and partaking in American society. In 1918, Marion Golde wrote an article in the American Jewish News titled “The Modern Ghetto Girl: Does She Lack Refinement?,” in which she stated that,

The fashionable dress of the East-side girl shrieks its cheapness and mimicry of the real thing… Her exaggerated coiffure, with its imitation curls and soaped curves that stick out at the side of the head like fantastic gargoyles, is offensive to the eye. Her plated gold jewelry with paste stones, bought from the Grand Street peddlers on pay-day reveles its cheapness by its very extravagance.6

The interest in clothes, fashion and style was a modern and American idea while old beliefs saw clothes as being modest and only a practical necessity. Sadie Frowne told of her experience of these conflicting views on the Lower East Side.

Some of the women blame me very much because I spend so much money on clothes. They say that instead of $1 a week I ought not to spend more than 25 cents a week on clothes, and that I should save the rest. Those who blame me are the old country people who have old-fashioned notions.7

She points out the conflicting beliefs within the Jewish community. Some believed that young immigrants were too eager to become American and were becoming less religious, turning their backs on orthodoxy. Rose Cohan writes that she arrived in the United States very religious yet over time became less devout. At one factory she worked at, the Jewish women were given Saturday off for Shabbat or the Sabbath. However, she writes, “I would have been willing to work for my religious scruples were gone.”8 This frightened her parents and like many other Jewish people, they believed their daughters were becoming too American and breaking too many traditions. Rose Cohan’s mother told her, “I would rather walk barefooted then that you should earn money while breaking the Sabbath.”9 However, many young Jewish immigrant women saw participation in United States society as a way forward to ‘becoming’ Americans.

There was another concern that the money young Jewish immigrant women made working in the garment industry gave them too much freedom. Although their wages were significant to their family’s income and stability, young Jewish women often did not get married right away and had a certain amount of autonomy from authority and in how they spent their money and time.10 This complicated the gender roles within their own community as marriage was an important part of culture and tradition, and young women were expected to become mothers and fulfill a role of being in charge of a home. Because young Jewish women needed to support their families they were seen as modern and turning away from traditional Orthodoxy. Sadie Frowne, tells that she has a boyfriend named Henry, “lately he has been urging me more and more to get married–but I think I’ll wait.”11 This was the modernity that was feared by both Jewish people and White Americans, as it also turned American femininity and traditional gender roles on its head. Around the turn of the century, White American gender roles cast men as breadwinners and as the ‘head’ of a family, while women stayed at home and were quiet and modest and sophisticated in their fashion. On the Lower East Side, young Jewish immigrant women, ‘Ghetto Girls,’ who dressed in cheap fashions many deemed to be tacky and vulgar, supported and were in many cases the sole breadwinner for their families and these gender roles cast a mark of Otherness and non-Whiteness and frightened White American society.

1. “Strikers And Stylemakers,” Tenement Museum, 2020, https://www.tenement.org/strikers-and-stylemakers/.

2. Sadie Frowne, “Days and Dreams,” Trianglefire.Ilr.Cornell.Edu, 2018. https://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/primary/testimonials/ootss_SadieFrowne.html.

3. Ibid.

4. Riv-Ellen Prell. “The Ghetto Girl and the Erasure of Memory,” in Remembering the Lower East Side: American Jewish Reflections, ed by Hasia R. Diner, Jeffrey Shandler, and Beth S. Wenger, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), 90.

5. “New York’s Biggest Problem, Not Police, But Girls; Immodesty, Extravagance, and Ignorance Are Among Their Characteristics, Says Miss Trenholm, Head Worker of the East Side Settlement,” The New York Times, August 4, 1912. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1912/08/04/issue.html.

6. Riv-Ellen Prell. “The Ghetto Girl and the Erasure of Memory,” in Remembering the Lower East Side: American Jewish Reflections, ed by Hasia R. Diner, Jeffrey Shandler, and Beth S. Wenger, 91-92.

7. Sadie Frowne, “Days and Dreams.”

8. Rose Cohan, Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side, Documents in American Social History (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995), 282.

9. Ibid., 256.

10. Riv-Ellen Prell. “The Ghetto Girl and the Erasure of Memory,” in Remembering the Lower East Side: American Jewish Reflections, ed by Hasia R. Diner, Jeffrey Shandler, and Beth S. Wenger, 96.

11. Sadie Frowne, “Days and Dreams.”