Dexter Gordon

June 3, 2020

African American Studies and the Race and Pedagogy Institute

PREAMBLE

You have seen my work and you have heard my voice in spaces across the Puget Sound campus, the city of Tacoma, and across the regions of the Salish Sea for almost 20 years.

You have heard me appeal to our entire campus –students, faculty and staff colleagues, the Board, and our partners in community.

I have written several letters, most of which I have kept to myself and my closest friends. Shared not even with my family.

Eighteen years ago, I started the work of Race and Pedagogy and the building of the African American Studies program with a public letter.

In response to crass racism on campus, I wrote to my faculty colleagues with the simple question – “What does race have to do with the development and delivery of your curriculum?” Alongside colleagues on campus and across our community, I have not stopped probing that question since.

Today, in the name of those who like me had their ancestors stolen from Africa and brutalized across the Americas, and to find my breath because George Floyd could not find his, I feel compelled to share another public letter.

I have started and revised this letter many times. I have had sleepless nights haunted by the image of another Black man laid out in the streets of America, dead. I am worried for my family. I am worried for my friends and communities. I am worried for my students. I am worried for my colleagues. I am worried for myself, for my life.

I have to speak. I have to write.

Should I begin with my outrage that no one should die the way 46-year-old George Floyd died, his body as one more spectacle and a mark of disdain for the humanity of Black people?

Protests have erupted and spread across the country. The police have responded harshly in some instances, but in some cases they have worked to diffuse tensions, most notably in Flint, Michigan. In Seattle, authorities are trying to find their way as they seek to affirm the efficacy of recent reforms in policing pressed for by local communities. The fact that some protests have spiraled into looting and violence, at times in the face of harsh police responses, has pushed the question of the role of violence expressions amidst civil disobedience in the search for justice to the forefront of our consideration. My life and that of my colleagues, committed to education and to social activism, is the testimony of my commitment to collaborative, cooperative, peaceful engagement as the best way to build strong, sustaining, inclusive societies.

But what if I start and stay here, for a while, and like Rev. William J. Barber II acknowledge that “No one wants to see their community burn. But the fires burning in Minneapolis, just like the fire burning in the spirits of so many marginalized Americans today, are a natural response to the trauma black communities have experienced, generation after generation.” This is human grappling, Black humanity grappling.

Perhaps, I should start instead with the long history of the ways in which the handcuffs on George Floyd’s wrists remind me of the chains of enslavement and exploitation of Black bodies, 12-15 million of us stolen from Africa. Or, I could go with the ways in which police officer Derek Chauvin’s knee on Floyd’s neck, in Minneapolis, on May 25, 2020, reminds me of the ropes used to lynch Black bodies, a practice that was at its heights one hundred years ago in America.

Maybe, I should reach back no longer than 69 years and begin with Langston Hughes’ cry.

“What Happens to a Dream Deferred?”

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

Or maybe, I should pair Hughes with Jayne Cortez’s searing lament from just eleven summers ago.

“There it is.”

My friend

they don’t care

if you’re an individualist

a leftist a rightist

a shithead or a snake

They will try to exploit you

absorb you confine you

disconnect you isolate you

or kill you…

Or should I go back to the militant Claude McKay, in the incendiary summer of 1919, “If We Must Die,”

with its forecast of 1921and 1923, Tulsa, Rosewood, and before them Atlanta, Georgia; Elaine, Arkansaas, and Colefax, Louisiana.

If we must die, O let us nobly die….

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

I am encouraged that many across the nation and in our own community are joining the incessant call for

equal rights and justice, the call to get up, to stand up.

I have to find words in this moment — for this moment — because as Jayne Cortez warns,

And if we don’t fight

if we don’t resist

if we don’t organize and unify and

get the power to control our own lives

Then we will wear

the exaggerated look of captivity

the stylized look of submission

the bizarre look of suicide

the dehumanized look of fear

and the decomposed look of repression

forever and ever and ever

And there it is

But, still searching, I wonder if I might turn to any of my children’s generation of lyrical expressionists Sa Roc, J. Cole, Jidenna, or one from this new generation. But here comes Nick Cannon, May 31, a bridge voice, who like the lyrical Black voices before and around him testify.

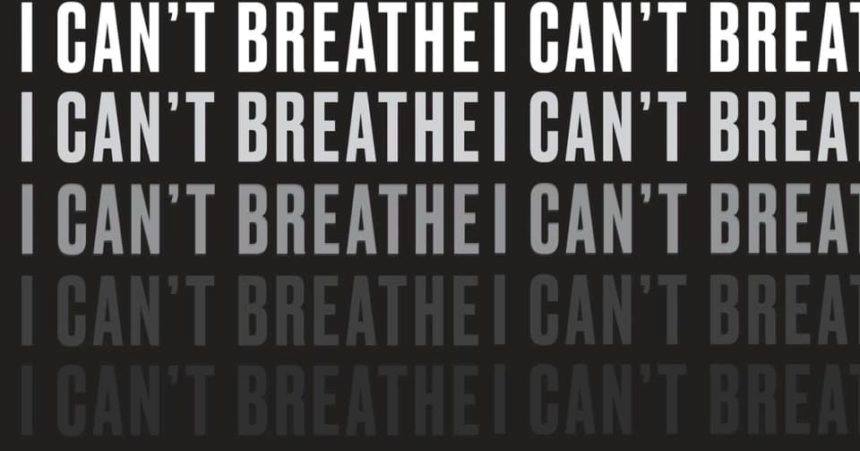

I can’t breathe again.

God damn, I can’t breathe.

Our voices are being quarantined.

Covid-1960s to 1619.

Jamestown choked me sold me.

Shackles hold me tightly by my neck.

And I can’t breathe again.

Still, the words, the words! The anguish. The pain. Will it stay or will it go away.

Probably I should stay with today and begin with the observation that trauma piled upon pain and suffering results in grief, anger, and explosive outrage. Since, over the last three months we have lived in horror and fear as COVID-19 rampaged through our communities and our world leaving in its wake death and destruction especially of the lives and livelihoods of Black and Brown people. The pandemic laid bare, long histories of neglect for Black and Brown communities. And then one more public killing.

I am haunted by the image of George Floyd pleading for life. So I consider starting with the ways in which George Floyd’s plea for a single breath, reminds me of 44-year-old Eric Garner gasping in the grip of a police choke-hold. Black people all across the world feel the pain and across America we feel suffocated –criminal justice, economics, health, education. I too feel like “I Can’t breathe.” I too feel the pain, a pain, it is one that connects directly to my own pain and sense of suffocation at University of Puget Sound. This is a subject I have not addressed publicly before.

My pain is born of the sense of disdain directed towards our work and the disrespect I experience from being passed over for opportunities to be appointed to lead in the work of equity on campus, repeatedly, for years, and again in this moment. This is a moment in which the University has decided it needs a Vice President for Equity Diversity and Inclusion, a position I have advocated for since 2007. There would not even be a question in any context of fairness that my expertise, experience, and my record of achievements make me the best candidate for such a role. In a world where equity and inclusion are valued, I would be urged to take on this assignment. Not so at Puget Sound. So even with the strongest recommendations from my peers and senior faculty in the work of equity, the University finds a way to pass me over without even meaningful consultation. Even as I write to survive this moment and continue to teach my classes, I have to be thinking about how to respond to this latest dissing and this continuing act of harm and erasure. As I watch, appointment after appointment, year after year, I wonder! Is there any fairness? Is there any justice?

This is my experience as the senior tenured Black faculty member at Puget Sound. I have provided almost twenty years of leadership on the campus on issues of equity and inclusion. Beginning in 2002, my work with colleagues has included inviting our campus to address the critical issues of race in our pedagogy. Since then, and including six years of significant work with Dr. Michael Benitez, who the university did not encourage to stay, despite his desire to, we have been in the forefront of addressing racism and all forms of inequities on our campus including in 2018 when we invited our campus and hundreds of participants from across the nation and beyond to join us for our National Conference on Race and Pedagogy, seeking to engage deep thoughtful reflection and practical impactful action on “Radically Reimagining the Project of Justice.” Re-imagining campus life. Re-imagining life.

Yet, the connection between the spectacle of another Black person killed while pleading for life, and the record of recent similar events, makes me want to begin with a statement against the killing of Black people by the police, including Black women, gender non-conforming and trans people. I want to declare solidarity with Black families and express sorrow at their loss, at our loss. I also wish to honor the memory of the many victims. The list is too long. The practice of killing is too serial.

George Floyd is only the most recent killing made public. In fact, the very next day, Wednesday, May 26, in Tallahassee, Florida, a Black trans man Tony McDade was shot and killed by the police. As Laura Thompson of Mother Jones points out, it is worth noting that in 2019, the American Medical Association deemed a surge in the murder of transgender people an “epidemic.” The vast majority of victims are transgender women of color. We honor their memories, alongside the memories of 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery, shot and killed, by two white men, while he was jogging in Georgia; Breonna Taylor, a 26-year old essential health care worker and aspiring nurse, shot eight times in her home by police. Strikingly, as campus leaders from UC Berkeley note “According to Rutgers University Sociologist Frank Edwards, one out of every 1,000 Black men in America will be killed by a police officer. This makes them two and half times more likely than white men to die during encounters with officers.”

So what does all this mean for us at the University of Puget Sound and the educational enterprise of which we are a part?

To begin, we must acknowledge that we are witnesses to this moment. We must take a position. Neutrality is not an option. We cannot avoid being implicated in this moment. President Crawford, in his May 30 statement, invites us to “make the world a better place, day by day, through our actions, our choices, and our care for one another.” There are also numerous other profound statements available from which to find inspiration. One way or another, to use the words of indigenous and environmental rights advocate, former Green Party vice presidential candidate, and 2014 RPI National Conference keynote speaker Winona LaDuke, “Find your voice. Find your courage.” We must find the will and the fortitude to act in ways that prevent a recurrence of this moment. This is a moment that in a literal sense represents the end of the rope for the many victims of ongoing systemic racism. Some victims are hidden in plain sight on our campus.

Another step then is to examine our own home and our own practices. An expression of solidarity with members of Puget Sound’s Black community is a meaningful step. We might then act with Black and Brown voices as leaders. Continually and consistently — not only when it serves as a symbolic gesture of inclusion — we should acknowledge them and their leadership in their areas of expertise and lived experiences. Difficult though it is, we should choose justice over comfort, resistance and rights over reputation. We may then begin to listen, really deeply listen to Black voices. Then believe what we say. We might act to redress historical harms caused to Black and Brown people by our University’s decisions and practices, past and present. We might go further and make sure that institutional actions do not perpetrate ongoing racist practices against Black and Brown people.

Finally, we might truly honor Puget Sound values and commit to the making and remaking of Puget Sound into an institution that acts intentionally to distance itself from the dastardly practices of white supremacy with its deadly surveillance and suffocation of Black and Brown bodies, and instead treat all people equitably and embrace respect as part of our new educational enterprise.

In African American Studies and the Race and Pedagogy Institute, this is our commitment. So this is where I’ll start.

To our beloved students, to faculty and staff colleagues, and to our partners in community, you matter.

We stand in solidarity with our and all Black communities and we are committed to treating each of you our Puget Sound students, colleagues, and partners with the respect and honor you deserve as part of our practice of education in partnership with you.

But for now

With appreciation for each of you and for every breath I am able to take.

Dexter Gordon